A HISTORY of SCANDINAVIAN TRADITIONAL FOLK WRESTLING by Tyr Neilsen

/ILLUSTRATION: THOR WRESTLES ELLI BY LORENZ FRØLICH

Throughout history, different forms of survival fighting skills have been developed all over the world, including hand-to-hand combat, designed for warfare situations when a warrior lost his weapon.

Without a weapon, a warrior could use his striking and wrestling skills for attack and defense or to hurt or kill an opponent. The most effective way for the weaponless warrior to defend himself, and attack, was by striking, seizing, off-balancing, and tripping or throwing the opponent to the ground.

These martial (war) techniques often inluded wrestling skills that could be used as sport. Over time they became traditional folk wrestling, which not only kept men fit and strong, but also became a source of entertainment, pleasure and play.

Wrestling was a big part of the Norse people's martial art. When used for fun, this wrestling became the most popular sport in Viking Age Scandinavia.

The earliest sources we have regarding Viking wrestling and Viking armed and unarmed combat are found in Norse poetry from the 9th century, a 12th century Icelandic manuscript known as the Younger Edda, and the Icelandic sagas.

According to the Icelandic Jónsbók lovboken (Jonsbok lawbook), compiled by Jón Einarsson in 1281, and based on earlier Norwegian Laws, the original settlers of Iceland took Viking wrestling and Viking combat techniques with them from their homeland, where they have been preserved as forms of folk-wrestling ever since.

TYPES of VIKING WRESTLING

There are 3 forms of Viking Wrestling that were practiced as íþrótt, which means sport in Old Norse. These forms of sport wrestling are defined by their grips; Lausatök, Hryggspenna, and Brókartök.

Lausatök in Old Norse means loose-grip, or free-grip. Lausatök is freestyle wrestling with rules. Lausatök was a liberal form of wrestling where all grips were permitted. Tricks were applied with the feet, hands and all other parts of the body. Various hand-grips, at least 27 of them, where also permitted. The contestant who remained standing won, if both contestants fell, the one who was quicker up again was the winner.

Lausatök is the basis for the armed and unarmed self-defense/combat martial art used by the Vikings. Lausatök was also used as the basis of Råbryting (raw wrestling) which was the most brutal form of sport wrestling in the Viking Age.

Lausatök was widely practiced in Iceland, until it was banned there in 1916 for being too dangerous. Lausatök remained popular in other Scandinavian countries, and in Norway, it continued to be more common than any other form of Nordic traditional folk wrestling. Today lausatök is the most popular form of Viking wrestling in Norway, Europe and USA.

Hryggspenna in Old Norse is back-grip. Hryggspenna is similar to back-hold wrestling, the most popular form of folk wrestling in Scotland, of which many regions were under Norwegian rule or colonization until the 15th century.

Viking hryggspenna relies on brute strength, and there are no throws, swings or any maneuvers which off-balance the opponent that are allowed. The wrestlers clasp their hands behind the opponent's back and they then try to sway the opponent back until he falls. Hryggspenna is a contest of strength, not of skillful techniques and agility.

Brókartök in Old Norse means trouser-grip. Brókartök is a form of rigid wrestling that has a permanent trouserbelt-grip. Brókartök is the most popular form of traditional folk wrestling in Sweden and Denmark, and a modern version of this is the national sport of Iceland.

Axlatök (shoulder-grip) is the name of a style from a single source (Þorsteinn Einarsson, 1984). According to this source, axlatök resembles Scottish back-hold in that axlatök wrestlers stand chest to chest overlooking each other’s right shoulder and clasp their hands high on each other’s backs. In axlatök, no other hand-grips or any hand-tricks are allowed, only swinging and foot tricks.

THE MYTH OF THOR IN THE SNORRA EDDA IS FOUND IN CHAPTERS 44–47 OF GYLFAGINNING. ( CHAPTER 46 MENTIONS GLÍMA )

The earliest introduction to Viking wrestling is found in the myth of Thor's journey to Utgard Loki, as it is told in ancient Viking poetry from the 9th century, by Bragi Hinn Gamli Boddason (790-850) and Kveldúlfr Bjálfason (820-878), both of Norwegian ancestry. Thor’s wrestling match is a highlight in this story, and the name of a technique is mentioned.

The oldest manuscript that mentions this myth is the Prose Edda, written by Snorri Sturluson (1178-1241) an Icelandic historian. According to Codex Upsaliensis, from the 14th century, Snorri's Edda is from around 1220. In the Norse myth, the thunder god Thor has a wrestling match with an old woman named Elli, which means "old age". She is described as an experienced wrestler and it is said that she has defeated stronger men than Thor. Elli uses throwing techniques called bragð, against Thor’s feet. When Thor starts to lose his balance, Elli tries to defeat him with very hard throw called sviptingar.

Thor falls down on one knee, and by touching the ground with the knee the fight is called as over by the judge Utgard Loki, who orders them to stop. We know this was a standing wrestling match, by the fact that the match was lost when anything other than feet touched the ground. This also tells us that there were rules and that wrestling was practiced also a sport/game.

Vikings loved all kinds of sports, but the best loved sport in Viking Age Scandinavia, was by far, wrestling. Wrestling was so important in Viking Age society, that their most popular god, Thor, was also the god of wrestling.

FANG - CATCH WRESTLING

There are references to Viking wrestling in the Icelandic law book Grágás, from the year 1117. The legal text makes it clear that everyone trains at their own risk, and that no athlete cannot blame others for damages incurred during training, unless an opponent has been proven as trying to hurt another opponent.

Viking wrestling is also mentioned in the Icelandic saga of Grettir the strong, where the combat is closely linked to the Nordic honor concept.

Viking wrestling is mentioned in eleven other Icelandic Sagas, such as Gunnlaugs saga ormstungu and Víga-Glúmssaga. In Finnboga saga ramma and in Gunnars saga Keldugnúpsfífls, there are stories of wrestling matches that took place indoors.

Before Egils saga, written around the year 1240, Viking wrestling is only mentioned by the name fang or fangbrögð in written sources. Fang in Old Norse means to catch, capure, embrace or hold.

Famntag, favnetag and favnetak were Swedish, Danish and Norwegian names for wrestling and have the same meaning as fang.

Taka fang in Old Norse means to take hold, which according to Snorra Edda, meant that opponents took one of the several fixed holds that would start a wrestling match.

At the annual Alþing (All-thing), a Viking Age assembly in Iceland where legal matters were settled, men wrestled for sport at Fangabrekka (Wrestling slope).

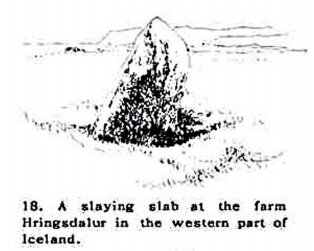

Some Viking wrestling matches were duel-like and fought to the death. Kjalnesinga saga tells of a wrestling match in Norway attended by the king. The fight took place on a wrestling field which contained a fanghella, a flat stone set on end, on which an opponent's back could be broken.

Medieval law-books are very good sources to find quality information about the laws and customs of society in that period. In the 11th century, the male population in Scandinavia was expected to be ready for military activities for their kings, and be competent in basic hand to hand combat and weapon combat, according leiðangr, the people's maritime military force, founded in Norway around the year 940. In this book Viking wrestling is defined as leikfang, which mean wrestling as play.

Leidangen was still in use until the 13th century, and there are references to the Viking martial art fighting style in the Norwegian Konungs skuggsjá, (King's Mirror) an educational text referred to politics and morals, published in the year 1250, and Hirðskrá, 'The book of the hird', a collection of laws regulating many aspects of the royal retinue from the end of 13th century Norway.

In the first part of the 1270's at the order of King Magnus VI, the Hirðskrá states that practical knowledge of martial arts is the most important virtue of a warrior.

In Heimskringla (the circle of the world) from Snorri's Old Norse kings' sagas, written in 1222, it is mentioned that Viking warriors were supposed to be vigr, meaning "able in battle" in Old Norse, at least until they were 60 years old.

ICELANDIC CHURCH and VIKING WRESTLING

In Egils saga, written around the years 1220-1240, the word glímur is mentioned. The noun glíma and the verb að glíma also appear in Finnboga saga (written in the early 13th century).

At this time, all styles of Viking wrestling, or fang, were practiced as sport or for fun, but Lausatök could be used to maim or kill, and was considered evil by the Icelandic church.

One source says that the name Glíma, an Old Norse word meaning joy, is believed to have been given to Viking wrestling by the clergy in the 11th century, in order to eradicate the remains of the heathen customs.

To be rid of the pagan sport/martial art, only brókartök, the trouser-grip version was acknowledged in Iceland. When glima is mentiooned in the Finnboga saga, it refers only to brókartök. Since then, brókartök has been made a gentler sport over time, and known as glíma in Iceland.

Viking wrestling had traditionally been practiced outdoors, and training in cold and icy conditions are part of what gave Viking wrestling its distinct grounded footwork and sharp movement.

Icelandic brókartök glima developed into a game that could be played indoors, where there was very limited space.

When glima was practiced in any natural place that gave shelter or indoors, these places were referred to as Glímuholl, meaning "Glima Hall".

THORLACIUS

From the medieval Edda manuscripts, and more recent historical combat manuals, all descriptions of Viking wrestling are presented as styles where arm techniques are as important as footwork, and the use of bragð (trick), kast (throw) as well as sviptingar (hard throw) and røsking (tugging techniques) are mentioned.

Through historical documents, we can see which Viking fighting techniques were still in use in the 1600’s, 1700’s and 1800’s.

The first scholar who wrote in detail about Viking wrestling, was the Icelander Skúli Þórđarson Thorlacius (1741-1815), who uses the term lausa-tauk when writing of Lausatök.

His work, Thorlacius' Borealium Veterum matrimonio, or 'the old Scandinavian customs of marriage' published in 1784, provides a thorough description of the ancient physical activities.

It is the fourth part of Antiqvitatum Boealium Observationes miscellaneæ or ‘miscellaneous observations of ancient Scandinavia’ that was published in seven parts 1778–1801 for the university students of Denmark.

Thorlacius separated these physical activities into three main groups - Ludi, Exercitia militaria and Pugnæ; Traditional games/sport, military exercises and combat.

Lucta, or wrestling, was the only activity belonging to both "Ludi" and "Pugnæ".

In his text, Thorlacius uses the terms fáng and glíma as the major expressions of Viking wrestling, the same words as used in Snorri's Edda manuscripts.

Thorlacius talks about two types of standing Viking wrestling forms; Lousatök (loose-grip/Free-grip), and rett glíma/fang (straight wrestling/trapping). He stressed the importance of sviptingar and braugd, and tells us that sviptingar belong to lousatök, and braugd to glíma/fang.

Fang has been translated as an Old Norse expression meaning ‘to wrestle’, which can be seen in the Scandinavian translations of Snorri’s Edda from the earliest 17th century editions.

‘Fang’ is a versatile word which could mean ‘trapping’, ‘catching’ or ‘fetching’ as an expression for grappling where a part of an opponent’s body is held, or an arm is trapped against the body.

Snorri’s Edda gives a clear idea of what ‘fang / glima’ is. Glima wrestling starts when the opponents ‘taka fang’ with each other. This indicates that grips or holds are to be taken when the opportunity presents itself. It also means that catching/fetching/embracing/trapping are its major action.

Thorlacius claims that straight glima/trapping differs from the others Viking wrestling styles because it relies more on ‘magis agilitate & exerciti’ (agility and exercise), instead of ‘qvam viribus nitens’ – through trials of strength.

‘Trick’ was a term used to describe martial arts techniques until the late 20th century. Thorlacius wrote that braugd were ‘varias supplantandi artes’, various tricks to trip the feet, that ‘strophas ac technas luctatorias habuit’ wrestling masters used.

Thorlacius also wrote about ‘Lucta brachialis’ meaning wrestling with the arms, which makes clear that this was wrestling that included leg and arm techniques.

Thorlacius also made it clear that this way of fighting is very versatile as contained ‘pancratii species fuit’, meaning wrestling and striking, and ‘impellendo raptandoqve’ , meaning offensive moves with brutal tugging, called sviptingar.

The aim of this style of wrestling was to be ‘adeoqve robore corpis maxime constabat’ (unwavering and to maximize the utilization of body strength).

In lucta ordinaria (straight glima/trapping wrestling), technical skills are favored above strength and aggressiveness which are found in lousat¨k. In the straight style, beinfeiinger (leg-sweeps) or braugder (tricks) play a major role.

The less restrictive style of lousatök (loose-grip/free-grip/freestyle) focuses on the offensive possibilities of the arms and the violent tugging movements, which can be done by a grip as well as by striking blow or kick.

Thorlacius wrote that lousatök was a form of pancratii, or combat style where every technique was used; wrestling as well as striking and other means.

Combat techniques from Scandinavian wrestling from the late 1700’s and early 1800’s shows that Thorlacius and Von Heidenstam had similar opinions on what Viking wrestling was all about.

Firstly, Scandinavian wrestling contains an arsenal of slagteknikker (strike techniques and powerful push techniques) against the chest, the throat and the neck, and that the throat, neck and chest are the main targets when striking above the waist.

A spark (kick) is used whenever possible, and the calf is the goal of both the sidespark (side-kick) and skyvespark (side and front thrust-kicks).

Beinfellinger (leg takedowns) are the most common leg techniques, such as beinkroker (leg hooks) and feiinger (leg-sweeps).

In wrestling situations using arms, the focus is set on attacking the legs. This means holding a leg or both legs with both arms, lifting the leg/legs to the side, and powerfully pulling the leg or legs upward.

Another arm technique that is also used is grabbing behind the knees and pulling, so that an opponent goes backwards to the ground. ‘Fattar hans lår med båda sina armar … lyfta det ena benet åt sidan … fattar hans venstra lår, och drar det strakt till sig ... fatta tag i venstra ben i knä vecket och rycka omkull honom’.

Thorlacius underlines the importance of glíma/fáng being seen both as a sport and a combat form. Thorlacius also identifies lousatök as a Viking wrestling style where everything is allowed and that the grappling action of combat glima as brutal and no nonsense.

Thorlacius demonstrated the basic principles and characteristics of glima, noted that the ancient Scandinavian form of glima was separated into two forms; sport and combat, and wrote: ‘lucta brachtialis, Borealibus lausa-tauk audiebat ... sic antiqvior’ (Lousatök is the oldest style of glima in the Scandinavian countries).

Thorlacius also confirmed that lousatök and rett glíma were still practiced in his time, 1741-1815.

LING

Per Henrik Ling (1776-1839) was master swordsman at Lund University 1805-1813 and Kalberg Military School from 1813 to 1826. In 1813, Ling founded Gymnastic Central Institute in Stockholm, which later became gymnastikk och idrettshøgkolan, the oldest school of its kind in the world.

In 1818 and 1835, Ling was appointed by the Swedish King as member of the prestigious Svenska Skolan, also known as "the eighteen", because of the very limited membership.

The Swedish and Norwegian military adopted the martial art system Ling based on traditional Scandinavian lousatök wrestling and combat techniques, and used them for bajonettkamp, (bayonet-fighting). This form of combat was directly related to Viking spear fighting.

HEIDENSTAM

In the years 1841-1842, the Swedish fencing champion Gustaf Daniel von Heidenstam (1785-1850) wrote a manual about Scandinavian wrestling titled Brottning (About Wrestling).

This wrestling manual was published in a limited edition in 1946 by Ling expert Carl August Wester Sheet (1873-1955).

Here, Von Heidestam wrote that Viking wrestling was a versatile and all-encompassing martial art. Von Heidestam wrote the manual in memory of his martial arts teacher, Per Henrik Ling.

Von Heidestam became the swordmaster at Kalberg Militærskole (Kalberg Military School) in 1808, until Ling took over in 1813. Von Heidestam was appointed swordmaster at Uppsala University the same year and held this position until his death in 1850 (University of Uppsala is the same university that owns the oldest Snorre Edda manuscript).

BALCK

Vikingbryting (Viking wrestling/Scandinavian wrestling) has always been practiced for combat in realistic situations, a fact mentioned in Illustrerad Idrottsbok (the illustrated sports book), published in three parts in 1886-1888 by Viktor Balck (1844-1928).

Balck was educated by Ling’s successor at Gymnasistiska Central Institute in Stockholm and is known as a founding member of the International Olympic Committee in 1894. When it came to the Viking/Scandinavian wrestling, Balck stressed the “importance of fair play, and that it should be done under strict rules”.

Balck also stressed that it should be “taken from a self-defense stance where all control techniques and techniques that could lead to throwing an opponent should be allowed and practiced".

Johannes Josefsson

ICELANDIC GLÍMA

Brókartök glíma (Trouser-grip glima) has been the official national sport in Iceland since 1906 and each year the winner receives the championship Grettís-beltí, (Grettis belt) named after the saga of Grettís, famous for its depiction of a glima battle in which two men fight against one.

The most famous Icelandic Glima Champion is probably Johannes Josefsson, Islands glima champion in 1907 and 1908. Josefsson represented Iceland at the 1908 Olympics in Greco-Roman wrestling.

Josefsson also went on to take part in a series of open martial arts tournaments, challenge matches, and had glima and wrestling demonstrations for royalty and for paying audiences worldwide.

Unbeaten in his lifetime, Josefsson wrote a technique-manual for Icelandic wrestling in 1908, describing many Glima moves.

GLÍMA AT OLYMPICS - STOCKHOLM 1912